Feel free to join our Trad-Egal online havurah, Coffeehouse Torah Talk

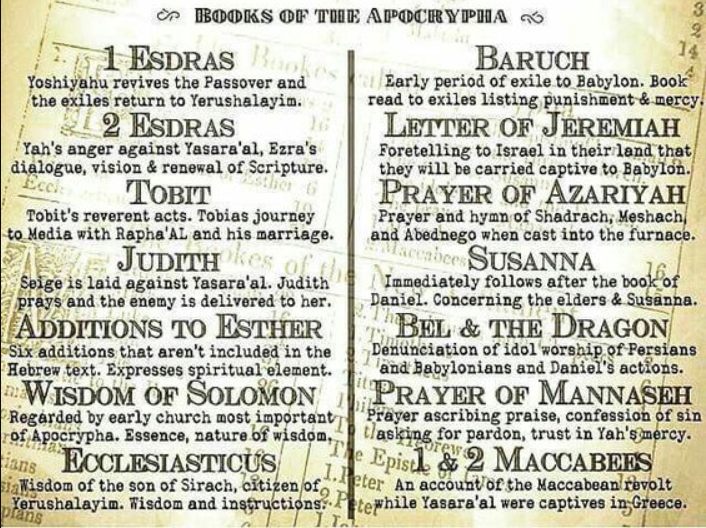

The Jewish apocrypha are a set of 14 or 15 (depends on the formatting) small books that were at one time almost accepted as part of the Jewish Bible, but did not become canonized. However, they are still religiously and historically Jewish works of literature, and they have a small role in Judaism.

Torah: Genesis (Bereishit), Exodus (Shemot), Leviticus (Vayikra), Numbers( Bamidbar), and Deuteronomy (Devarim).

Nevi’im (Prophets): Joshua, Judges, I Samuel, II Samuel, I Kings, II Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Joel, Amos, Obadiah, Jonah, Micah, Nahum, Habukkuk, Zephaniah, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi. (The last twelve are grouped together as “Trei Asar”, the twelve.)

Ketuvim (Writings): Psalms, Proverbs, Job, Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemiah, I Chronicles, II Chronicles.

What is the Septuagint and apocrypha?

In ancient Israel, there were two similar versions of the Tanakh . The version used in the land of Israel was basically the version we have today. A slightly longer version was accepted in the Jewish community of Alexandria, Egypt, during the last 3 centuries BCE. It had 15 short additional books (most were quite short) This version is the Septuagint, and it existed as a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. About one million Jews lived in Egypt during this era.

Over time, the additional 15 books were eventually rejected as being non-canonical. Jews never rejected them as meaningful; they just were not considered to have been written by prophets. But these extra 15 texts were occasionally read and sometimes religiously used by later generations of rabbinic Judaism.

So what are the 15 books of the Jewish apocrypha?

Esdras (Ezra)

The Tanakh [Hebrew Bible] has one book called “Ezra-Nehemiah”. Christians split this into two books, Ezra (called Esdras I by Catholics) and Nehemiah (called Esdras II by Catholics). For Jews these are canonical parts of our Bible.

There are two other books on the same subject that are part of the Jewish apocryphal. They go by different names.

- Esdras III (Catholics name) 1 Esdras (Protestant name) or Esdras A (Greek Orthodox name).

- Esdras IV (Catholic name), 2 Esdras (Protestant name) and Esdras B (Greek Orthodox name).

III Esdras / 1 Esdras / Esdras A

Except for one section (3:1-5:6), which is not found elsewhere in the Tanakh, this book is a Greek paraphrase of a Hebrew text containing the canonical Book of Ezra, part of chapters 7 and 8 of the canonical Book of Nehemiah, and 2 Chronicles 35:1-36:21. Scholars believe that it was produced between 150 and 50 BCE. Starting with an account of the Passover of the Judean king Josiah, III Esdras (1 Esdras) tells of the subsequent decline of Judah, of the Babylonian Captivity (Babylonian exile), and of events in Jerusalem immediately following the exile. (c)

The one major addition in this book is the story of “The Debate of the Three Youths”. It is an adaptation of a Persian story. In it, Zerubbabel, the guardsman of Darius, wins a debate with two other young men over who the strongest power might be: wine, the king, or, as Zerubbabel said “women are strongest, but truth conquers all.” By winning this debate, Zerubbabel is able to remind Darius of his obligation to allow the rebuilding of the temple. (b)

IV Esdras / 2 Esdras / Esdras B

A combination of wisdom and apocalyptic literature, this book was composed near the end of the 1st century CE, some 30 years after the Roman destruction of Jerusalem. It was never a part of the Septuagint, but many Churches give it deuterocanonical status. It examines the conflict between religious faith and the reality of evil, gives apocalyptic visions of the future of Israel and its redemption, and an account of Ezra’s editing of the Hebrew Bible. The text was later framed by the addition of two chapters at the beginning and one at the end by a Christian writer around 150 CE.

Tobit (Tobias)

A fictional narrative depicting the life of an exiled Israelite family (Tobit, Tobias and Sarah) living in Ninenveh, capital of the Assyrian Empire, during the 7th century BCE. Tobit demonstrates that God hears and answers the prayers of his landless and dispossessed faithful. Historians believe that it was written around 180 BCE. (a)

Judith

An anonymous historical romance, Judith resembles Esther in depicting the dangers of Jews living in the diaspora. Set during the Assyrian threat to Israel, the book presents Judith’s killing of Holofernes as an act of national heroism. Historians believe that in this book the character of Nebuchadnezzer represents Antiochus IV, who shortly before this work was written has tried to eradicate Israel’s religion (I Maccabees 1, Daniel 3). Judith was probably written around 150 CE, about a decade after the Maccabees had successfully repulsed the Syrians. (a)

“Additions to the book of Esther”

An unknown editor interpolated prayers and pious sentiments into the essentially secular Book of Esther, which originally did not even mention God. The Septuagint version of Esther contains six additions not found in the Hebrew original. Most scholars believe that these additions were not composed until around 114 BCE, when Esther was translated into Greek. The Septuagint editors interspersed the additions at various points in the story, but when Jerome prepared the Latin Vulgate he removed the additions from the main body of the work and placed them at the end. (a)

The Wisdom of Solomon

A collection of poems, proverbs and meditations, composed by an anonymous Hellenized Jew living in Alexandria, Egypt, during the last century BCE. A creative synthesis of Hebrew wisdom traditions with speculative Greek philosophy, the book surveys the nature of divine wisdom and immortality it departs, and describes the origin, character, and value of Wisdom. It was aimed at Jews living in exile, some of whom were tempted to compromise or relinquish their religion under the allurements of Greek culture. (a)

The Wisdom of Sirach / Sirach / Ecclesiasticus / Ben Sira

A poetic compilation of proverbs, sage advice, and philosophical reflection, this was written early in the 2nd century BCE by Jesus (Joshua) son of Sirach, the head of a wisdom school in Jerusalem. The longest wisdom book in the Bible, it is also the only apocryphal writing whose author, original translator and date are known. It contains moral essays, hymns to wisdom, practical advice to the young, instructions in proper social and religious conduct, and reflections on the human condition. (a)

Baruch

A composite work by two different writers (three if you count the letter of Jeremiah as its last chapter), Baruch purports to be a prophetic document written by Jeremiah’s secretary early in the Babylonian captivity. It includes a prayer of the Jewish exiles, a hymn to wisdom, and religious poems. Baruch is the only book of the apocrypha whose mode resembles the prophetic. The books parts have been dated from about 200 BCE for the earliest parts, to after 70CE for the later additions. (a)

The letter of Jeremiah

Although some ancient manuscripts place this as a separate document after the book of Lamentations (Eicha), the Latin Vulgate and most English translations place this as the last chapter of Baruch. In that counting scheme, there are then 14 Jewish apocryphal works, not 15. Purporting to be a letter from Jeremiah to Jews about to be deported to Babylon it in fact is a much later work, apparently modeled on Jeremiah’s authentic 6th century BCE letter. Estimates of the date of composition vary from 317 to 100 BCE. (a)

The additions to Daniel

The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three

Susanna

Daniel, Bel and the Dragon

The Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three

The prayer of Azariah

(the Hebrew name of the man whom King Nebuchadnezzar called Abednego) is a lament confessing Israel’s collective sins and beseeching God for mercy, through the psalm strangely never alludes to Azariah’s fiery ordeal. The poem may have been composed during the persecutions of Antiochus IV, perhaps about the same time the apocalyptic portions of Daniel 7-12 were written (a).

The song of the three (Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego/Azariah)

was said to be sung by the three while they were confined in a Babylonian furnace. It is a hymn of praise extolling the God of their ancestors, and inciting the natural elements to praise God. Some have suggested that this poem – which resembles Psalm 148 in thought and Psalm 136 in form – may have been a popular form of Thanksgiving for the Maccabean victories. Experts are not agreed, however, on the exact time of composition. They are approximately from the late 2nd or early 1st century BCE. (a)

Susanna

Susanna is a beautiful and virtuous wife of a wealthy Jew in Babylon. Two Jewish elders lust after her when they come upon her while she is taking a bath; they demand that she have sex with them, or they say that they will accuse her of being an adulterer. She chooses the latter. The two men who have accused her are believed in court, and she is sentenced to death, but God inspires Daniel to demand a more comprehensive investigation. He separates the two elders and questions them separately. They give contradictory testimony, which exonerates and frees the woman. Further, they are convicted of perjury and executed. Some scholars believe that this tale was written to criticize corrupt judges.

Bel and the Dragon

A prose account of three incidents. Daniel proves to King Astyages (Cyrus of Persia) that the great statue of Bel (The Babylonian God Marduk) does not eat the food left before it, but that the offerings are actually consumed by lying priests. Later, Daniel poisons a dragon or large serpent, to show his credulous ruler that it is not a God but a mortal reptile. When it is learned that he has done this, the Babylonians – who worshiped the dragon – persuaded the King to punish Daniel by throwing him into a den of lions for six days. Due to angelic intervention, Daniel is not harmed. Upon discovering this, the King releases Daniel and praises his God. This story was probably written in order to ridicule the belief in pagan Gods.

The Prayer of Manasseh

Manasseh is remembered as one of the worst kings of Judah because of his worship of foreign gods (2 Kings 21:1-18). According to 2 Chronicles 33:10-17 Manasseh was said to have been taken captive by the Assyrians. Manasseh is said to have repented while in prison, and the book known as the Prayer of Manasseh gives an account of his prayer. The king praises God, confesses his sin, requests mercy, and then praises God again. Chronicles says that Manasseh was eventually restored to his throne and that he undertook reforms, showing that God heeds those who repent. The date of origin of this work is unknown. It was never a part of the Septuagint, but many Churches give it deuterocanonical status.

1 Maccabees

A fairly accurate history of the Jewish revolt against Greek-Syrian oppression; it covers the events between 170 and 134 BC, concerning the struggle of the Jews against Antiochus IV (Epiphanes), the wars of the Hasmonaeans, and the rule of John Hyrcanus. It describes the origin of holiday celebrating the rededication (Chanukah) of the Holy Temple. 1 Maccabees gives an apparent eyewitness description and remarkably unprejudiced account of the fight for religious freedom. It is notable for its plain, swiftly moving style, and the complete absence of miracles and supernatural elements. (a)

2 Maccabees

An expanded revision of the first seven chapters of 1 Maccabees, it covers the years approximately 170- 160 BCE. 2 Maccabees is a theologically oriented reinterpretation of events, emphasizing tales of official corruption, persecution and the integrity of martyred Torah loyalists. It interpolates many religious beliefs into the narrative. It is a Greek work, probably written in Alexandria, Egypt, about 124 BCE. (a) “To the Historians of Judaism and Christianity the book is especially important because in addition to statements about the observance of the Sabbath, and other practices that may be said to reveal a Pharisaic point of view, it contains what are probably the earliest explicit references to the resurrection of the body [after death]. (e)

Other books called “Maccabees” exist, but they were not part of the 15 Jewish Books of the apocrypha: These are III and IV Maccabees. They were never part of the Septuagint accepted by the Jewish community of Alexandria. These latter two books were only accepted, much later, by Christians, so they exist in the category of Christian apocrypha (which is better treated in other articles.) They are found in some manuscripts of the Septuagint.

III Maccabees is not included in the Vulgate version or the King James version, and is therefore less known to English readers…the word “Maccabees” is misleading since the book is concerned with the Jews of Egypt and has nothing to do with the Hasmoneans…[it] supposedly dates from the reign of the Macedonian King of Egypt, Ptolemy IV Philopator (221-302 BCE)….[Some authorities believe that it was written by] an Egyptian Jewish writer of the 1st century BCE who has combined events of the reigns of two different kings, and has added picturesque details suggested by the Book of Esther and II Maccabees. (e) This work is accepted as deuterocanonical by many Eastern Orthodox churches.

IV Maccabees was written near the beginning of the first century CE by an Alexandrian Jew with a knowledge of Greek philosophy. “It is a sermon on the theme that reason can control passion. This argument is illustrated by examples taken from Jewish history, especially of the Maccabean period. Though this book…is included in three of the oldest and most important manuscripts of the Greek Bible, it was (mistaken;) regarded by [many] early Church fathers as the work of Falvius Josephus; for this reason it is not found in the Latin Bible and consequently is not counted among the apocryphal books of the English and other modern versions of the Bible. IV Maccabees seems to have been entirely unknown to the Jews until modern times….Like Aristobulus and Philo, the author is trying to show that the great virtues of the Platonic-Stoic tradition are to attained by observing the Law of Moses. (e) Only a small number of Eastern Orthodox churches accept it as deuterocanonical.

What do the Talmud and Midrash say about the apocrypha?

There is one place in the Talmud where Rabbi Akiva states that

it is heretical to read from the “outside works”; this phrase has been understood by manu to refer to the books of the apocrypha. In truth, this identification is not accurate; there is some reason to believe that he may have been referring to other books, possibly even some of the books that later become part of the Tanakh [Hebrew Bible]! For more details on this issue, consult the Encyclopedia Judaica’s section on “Apocrypha”.

In either reading, his view was not accepted as law, and many other sages of the Talmud and midrash felt free to read and discuss the works of the apocrypha, especially the Wisdom of Ben Sira [aka Ecclesiasticus] and Maccabees. Note that even one of Judaism’s most beloved holidays, Chanukah, is based on the events described in I and II Maccabees. For some examples of rabbinic discussions of apocryphal works, see the following rabbinic sources:

Talmud Yerushalmi: Hagigah 2;1, 47C; Berakhot 7:2, 11b

Talmud Bavli: Hagigah 12b, 13a; Berakhot 48a; Shabbat 21b; Yevamot 63b, Ketubot 110b, Bava Batra 98b

Midrash: Genesis Rabbah 91:3,

Responsa of the Rishonim: Tosfot Eruvin 65b; Ritva Eruvin 65a; Rashba Eruvin 65a; Meiri Nidda 16b

Nahmanides quotes “The Wisdom of Solomon in the introduction to his commentary on the Torah. “The Wisdom of Solomon” is also cited in “Livnat HaSapir”, a Torah commentary attributed to David ben Judah HeHasid. The midrash collection “Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer” makes use of the apocrypha.

How has the apocrypha entered the Jewish liturgy?

The works of the apocrypha have been used as the basis for two important parts of the Jewish liturgy. In the Mahzor [High Holy day prayer book], a medieval Jewish poet used Ben Sira as the basis for a beautiful poem, Ke’Ohel HaNimtah. This is a closing piyut in the Seder Avodah section, in the Yom Kipur Musaf. It begins “How glorious indeed was the High Priest, when he safely left the Holy of Holies. Like the clearest canopy of Heaven was the dazzling countenance of the priest” (This can be seen, for example, on page 828 of the Birnbaum edition of the Mahzor.] The Conservative Mahzor replaces the medieval piyyut with the relevant section from Ben Sira, which is more direct, and just as beautiful.

The apocrypha has even formed the basis of the most important of all Jewish prayers, the Amidah [the Shemonah Esrah]. Ben Sira provides the vocabulary and framework for many of the Amidah’s blessings, which were instituted by the men of the Great Assembly. For more information, see these works:

Joseph Heinemann “Prayer In The Talmud” (Berlin, 1977), p.219

“Amidah”, Encyclopedia Judaica, 1971

Reuven Hammer “Entering Jewish Prayer” (Schocken Books), p.86, 309.

Sources

(a) Understanding The Bible (3rd edition), Stephen L. Harris

Mayfield Publishing Company, , 1992

(b) From the entry “Esdras” by Charles L. Souvay, in the Catholic

Encyclopedia, 1913, the Encyclopedia Press, Inc.

http://www.knight.org/advent/cathen/05535a.htm

(c) From the online Encarta Concise Encyclopedia

http://encarta.msn.com/index/conciseindex/4e/04ed9000.htm

(d) Old Testament Life and Literature (1968) Gerald LaRue

(e) “Hellenistic Jewish Literature” by Ralph Marcus, printed in

“The Jews: Their History, Culture and Religion” Volume II, (3rd

edition). Edited by Louis Finkelstein, Harper and Brothers, NY 1960

(f) “Apocrypha” Encyclopaedia Judaica