The Talmud, which includes the Mishnah, is the core text of rabbinic Judaism. Learners find it challenging to understand unless learning alongside a teacher, or with a detailed commentary.

The Talmud is an enormous document, covering centuries of rabbinic debates, hand written and edited, long before the invention of the printing press. In order to make it a practical size, it had to be encoded in a hyper condensed style. Arguments and methods of thought are often represented with a term or brief phrase; quotations from the Torah, Tanakh or Mishnah are brief: the text assumes that the reader is familiar with the entire corpus of Bible and rabbinic literature. The document is effectively hyperlinked – each section assumes that the reader knows which other sections the text refers to. Even so, the Talmud is the size of an entire encyclopedia.

It is instructive to compare the bare text of the Talmud, to how it is explained by a master teacher, who brings in the relevant material necessary to understand the text.

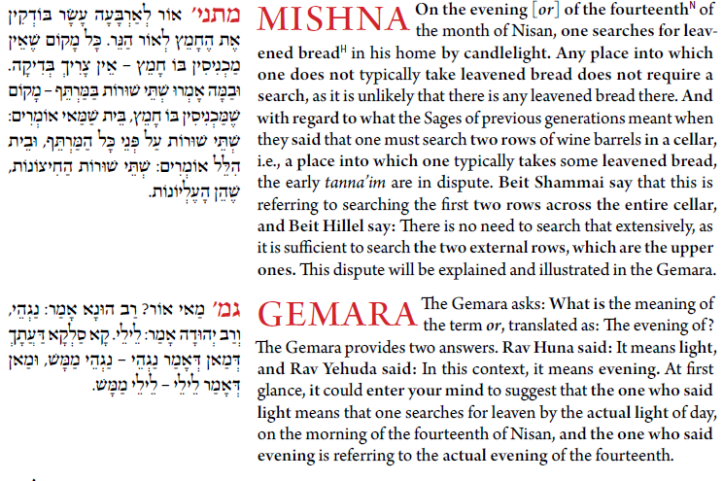

Here is an excerpt from the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Pesachim, from the famous Soncino Edition. It’s translation comes close to a literal, sometimes word-for-word rendering of the text:

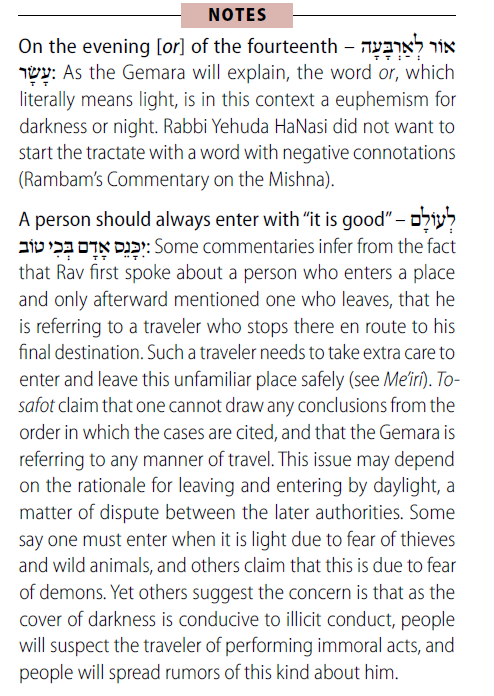

MISHNAH. ON THE EVENING [OR] OF THE FOURTEENTH [OF NISAN] A SEARCH IS

MADE FOR LEAVEN BY THE LIGHT OF A LAMP. EVERY PLACE WHEREIN LEAVENED

BREAD IS NOT TAKEN DOES NOT REQUIRE SEARCHING, THEN IN WHAT CASE DID

THEY RULE, TWO ROWS OF THE WINE CELLAR [MUST BE SEARCHED]?

[CONCERNING] A PLACE WHEREIN LEAVEN MIGHT BE TAKEN, BETH SHAMMAI

MAINTAIN: TWO ROWS OVER THE FRONT OF THE WHOLE CELLAR; BUT BETH

HILLEL MAINTAIN: THE TWO OUTER ROWS, WHICH ARE THE UPPERMOST.

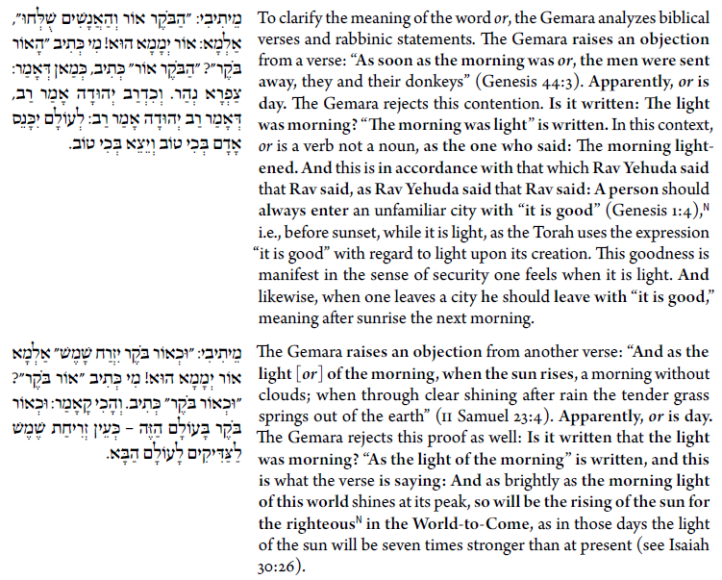

GEMARA. What is OR? — R. Huna said: Light [naghe]; while Rab Judah said: Night [lele]. Now it was assumed [that] he who says light means literally light;8 while he who says night means literally night.

An objection is raised: As soon as the morning was light [or], the men were sent away, which proves that ‘or’ is day? — Is it then written, The ‘or’ was morning: [Surely] ‘the morning was or’ is written, as one says, Morning has broken forth. And [this verse is] in accordance with what Rab Judah said in Rab’s name. For Rab Judah said in Rab’s name: A man should always enter [a town] by day, and set out by day.

An objection is raised: As the light of [or] the morning, when the sun riseth, which proves that ‘or’ means the daytime? — Is it then written, ‘or is morning’: surely it is written, ‘as the light of [or] the morning’, and this is its meaning: ‘and as the light of the morning’ in this world so shall the rising of the sun be unto the righteous in the world to come.

What does this all mean? What precisely are the arguments being made?

The Steinsaltz edition of the Talmud – which has been published in several different editions (Modern Hebrew, French, English – from Random House, and English – from Koren) is something of a modern legend, used in Modern Orthodoxy, Chabad Lubavitch, and Reform and Conservative Judaism. Here we present the same Mishnah and Gemara – but this time including the Koren edition’s introduction and translation/commentary: the commentary has the more literal parts in bold-face, while interpolated explanation is in non-bolded font.

Introduction:

The Torah prohibits the possession of any leaven or leavened bread throughout the

week of Passover, mandating its removal beforehand. However, the correct way to

practically fulfill these obligations is left undefi ned. At what point before the Festival

is a person obligated to remove leaven from his or her possession? How should this

be done?

Furthermore, what is the legal definition of leaven being in one’s possession? The

Torah formulates the prohibition by stating that leaven or leavened bread should

not be found in one’s house or quarters. This raises the question of leaven that is

physically found in one’s property but is owned by a gentile: Does such leaven have

to be removed? Similarly, what should be done with the leaven in order for it to be

considered removed from one’s possession? Is it necessary to physically remove or

destroy it, or is it suffi cient to renounce ownership or nullify it? Many of these questions

are addressed in the first chapter of tractate Pesaĥim.

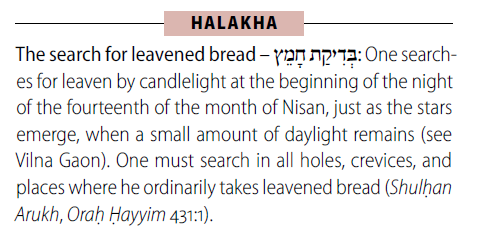

Although the Torah requires only that the leaven be removed from one’s possession,

the Sages enacted that a search be conducted and that all leaven be identified, in order

to ensure its removal before the onset of the Festival. What method should be used?

When should the search ideally be conducted, and is it valid if conducted at other

times? Who is obligated to perform the search, especially in cases where more than

one person is responsible for a property? A full discussion of these issues provides

a major focus of this chapter.